Introduction to Bacon & the Art of Living

The story of bacon is set in the late 1800s and early 1900s when most of the important developments in bacon took place. The plotline takes place in the 2000s with each character referring to a real person and actual events. The theme is a kind of “steampunk” where modern mannerisms, speech, clothes and practices are superimposed on a historical setting. Modern people interact with old historical figures with all the historical and cultural bias that goes with this.

investigative – academic – background

The Kune Kune

June 1893

Dear Kids,

I left London infused and inspired by the Harris family and their bacon empire! When we arrived in New Zealand I was convinced that I would find footprints of C & T Harris or at least Oake-Woods. The first footprints we found were, however, of a different nature. It was the footprints of a remarkable creature that took me back to my childhood days on Grandpa and Grandma Stillehoogte Farm in the North Free Sate. The creature was the Kune-Kune pig from New Zealand which looked to me almost identical to the Kolbroek at the Cape.

Pigs and Butter

As is the case around the world, pigs are a very useful dance partner with the dairy industry. Berkshire is the most popular breed on these islands. The large and small breeds of White Yorkshire are also bred, but they are not as popular as the black pigs. Many farmers don’t breed the pigs; they only rear and fatten them, which has proved to be a very lucrative business. The New Zealand pigs are heartier than those from England and unlike the English pigs, they only need a good grass paddock, with an abundance of roots, a small quantity of unthreshed pea-haul for finishing them a few weeks before the killing, and of course, lots of water with good shelter from the sun during the warmest summer months.

The pork industry is beneficial to dairy and brewery industries since it provides a way to dispose of low-value by-products such as whey protein, a by-product in cheese making and brewery waste which otherwise must be discarded. Another reason a healthy pork industry is a benefit to the farmer is that it provides an effective way to deal with inferior grain which may be converted into mutton and pork. It is not a good practice to pay freight on inferior samples of grain; it will pay far better to convert it into mutton and pork, which may be driven to market on four legs, instead of four wheels. The rule applying to the dairy produce — namely, that it should be of the finest quality — applied with equal force to grain intended for shipment.

After our wedding, Minette and I visited a few large pig farmers who farm close to Cheviot and Gore Bay. It was here that I came face-to-face with the Kune-Kune.

The Kunekune

To my great surprise, we found a pig breed on the Islands, very popular amongst the Māori, that looks almost exactly like the Kolbroek breed of the Cape. Kunekune is a Māori word meaning “fat and round” and it perfectly describes this adorable and mild-tempered animal.

Let me first show you what I mean when I say that they look exactly like the Kolbroek.

-> Compare the Kune Kune photos, courtesy of the Empire Kunekune Pig Association of New York.

-> Compare these with the Kolbroek, photos with the courtesy of Zenzele Farm in South Africa.

I wonder if the Kolbroek which came to the Cape of Good Hope is, in essence, the same pigs (group or breed) that also arrived at the shores of New Zealand? How does it happen that these pig breeds look so strikingly similar? I wonder if I, as a foreigner and not a Kunekune, Kolbroek or pig breeding expert can venture a guess how it could have happened that these animals look so similar.

Form of the Kunekune Compared with Drawings from England

I find the comparison between the form of the Kune Kune with the Berkshire and Large White very interesting.

Kune Kune Sow and Piglets by Elisabeth Sequoia

Large White

Berkshire Pigs

Uniting the Kolbroek, the Kunekune, the English East Indian Company, and China

We know that the Kunekune has Chinese genes. An obvious link between the Kunekune, the Kolbroek, and China from the 1700s is the English East Indian Company and possibly the English Navy. The English East Indian Company is the most obvious organisation of that time which facilitated trade between England and China. It makes sense that they were responsible for populating England with Chinese pigs. It also stands to reason that it was an English East Indian ship that was responsible for ferrying the fletching nucleus of pigs of what would become the Kolbroek to Kogel Bay at Cape Hangklip where runaway slaves possibly took over the small herd which swam ashore off the sinking Colebrook and were responsible for initially preserving them (Kolbroek).

If the Kunekune came to New Zealand around the same time and also from an English East Indian ship or from the English navy; if the New Zealand pigs were also taken on board from Gravesend as the evidence seems to suggest was the case with the Kolbroek pigs; if the pigs were not breed-pigs like the Berkshire or the Buckinghamshire but, as I suspect, village pigs from Kent; this will explain the Chinese connection and how these seemingly very close relatives made it to both South Africa and New Zealand. One would expect to find evidence in the genetic makeup of the breeds, both Chinese and European origins.

Considering the facts before us leads to this very intriguing and neat conclusion and would settle the matter of the origins of the Kolbroek based on the strong similarities between the Kolbroek and the Kunekune. It would preclude the possibility that the Kolbroek “evolved” through a complicated cross-bearding of Chinese or Portuguese, Spanish or Dutch breeds with South African wild boars or even warthogs. Let’s delve into the facts.

China

I have written to you previously about the development of the English Pig when Minette and I met Michael in Liverpool while we stayed at the Royal Waterloo Hotel (The English Pig with links to the Kolbroek and Kunekune). I do not wish to repeat myself except to remind you that around eight thousand years ago, pigs in China made a transition from wind animals to the farm. They started living off scraps of food from human settlements. Humans penned them up and started feeding them which removed the evolutionary pressure they had as wild animals living in the forest. They were bred by humans instead of being left in the forests to breed naturally and to fend for themselves. This led to an animal that is round, pale, short-legged, and pot-bellied with traditional regional breeding preferences that persist to this day. (White, 2011)

In contrast to the Chinese custom, in the West, the scavengers were treated differently. There is evidence that pigs were initially exploited in the Middle East around 9000 to 10 000 years ago. These denser settlements of the Neolithic times in the fertile crescent did not pen the animals up but ejected them from their society. The pigs may have been a nuisance or competed with humans for scarce resources such as water. Genetic research shows that the first pig exploitation in Anatolia (around modern-day Turkey) “hit a dead end.” (White, 2011) The pigs that were domesticated here all died out.

The pigs in Europe and England were kept in the wild for extended periods of time. Various European populations developed techniques of mast feeding (Mast being the fruit of forest trees and shrubs, such as acorns and other nuts). Herds were pushed into abandoned forests and feeding them on beechnuts and acorns that are of marginal value to humans. (White, 2011)

The practice of pannage, as it is called, is the releasing of livestock pigs in a forest, so that they can feed on fallen acorns, beech mast, chestnuts or other nuts. One of the requirements for a Chinese/ European pig breed to have survived either in South Africa or New Zealand as a distinct breed is that the pigs did not become part of the general pig population, dealt with according to European custom, but, instead, was kept according to Chinese traditions in pens. The “pressure” to keep them in pens instead of letting them run wild as was the custom at the Cape, I believe was that the pigs were received by runaway slaves who knew pig husbandry and kept the pigs penned up as they did with other domesticated animals on their hideouts as a way to keep them “close” and out of sight of the general farm population for fear of being detected by authorities and the slaves be re-captured. The question is if there existed similar pressure in New Zealand.

The most likely candidate to have taken the pigs from England to the Cape was the Colebrook in 1778 and Captain Cook, who is known to have released pigs on islands he visited, is the most likely candidate to have ferried the ancestors of the Kunekune to New Zealand. The pigs that he released on the middle Island who was not penned up but roamed the forests became feral and their characteristics changed to revert back to the wild state. We know that crossbreeds between Chinese and European breeds appeared in England well before the 1778 sailing of the Colebrook for the Cape of Good Hope and the three visits of Cook to New Zealand, in 1769-70, 1773 and 1777.

Kunekune

We have already seen that the Kunekune and the Kolbroek can be one pig breed for all intents and purposes. What is there that we know about the genetics of the Kunekune? A paper was presented by Gongora, et al., at the 7th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, Montpellier, France, (2) entitled Origins of the Kune Kune and Auckland Island Pigs in New Zealand.

They introduce their paper as follows, directly addressing the matters of interest to us. “Migrating Polynesians first introduced pigs from Asia to the Pacific islands (Diamond, 1997), but it is not clear whether they reached New Zealand. European sailors and settlers introduced pigs into New Zealand in the 18th and 19th centuries, many of which became feral, but few records were kept of these introductions (Clarke and Dzieciolowski, 1991a; 1991b). It is believed that the European settlers introduced contemporary domestic animals originating either directly or indirectly from Europe (Challies, 1976).” (Gongora, 2002) It is this last possibility that is of interest to us. If the DNA evidence supports this possibility, it opens up the link with the Kolbroek since both pigs have prominent Chinese in their DNA and both possibly originated from Europe.

One must be careful here since Cook got pigs from many parts of the world and others are known to also have sent pigs to New Zealand. The possibility, for example, that the Kunekune came from pigs that Captain Cook released on the South Island in 1773, obtained from Tonga and Tahiti, and, therefore, undoubtedly of Polynesian origin (Clarke and Dzieciolowski, 1991a) remains. (Gongora, 2002)

Gongora, and coworkers et al. (2002) report that the “unequivocal Asian origin of the Kune Kune mitochondrial sequence is consistent with the pigs being taken from Asia to New Zealand by the Polynesian ancestors of present-day Maoris, but maybe better supported by the well documented introduction of Polynesian pigs into New Zealand by Captain Cook in 1773.” (Gongora, 2002) This is, of course, the most obvious conclusion.

However, the possibility of the introduction of this Asian mitochondrial sequence via a European breed, which acquired Asian mitochondria by introgression in the 18th century in Europe is as good a possibility as the aforementioned. (Gongora, 2002) Gongora says that “such introgression explains the clustering of the Large White and Berkshire sequences with Asian pigs” as can be seen from the graph below.

Nucleotide substitutions and gaps are found in 32 porcine mtDNA D-loop sequences. The Kune Kune clusters with Asian domestic pigs are most closely related to Chinese and Japanese breeds. The Auckland Island sequence clusters with domestic European breeds (Gongora, 2002). Auckland Island is situated south of New Zealand and it is thought that the pigs that were released there may have the same origin as the Kunekune.

“Analysis of additional Kune Kune sequences as well as more Polynesian sequences may help distinguish the first two possibilities from the third. Finding unambiguous Polynesian sequences may be difficult though, as Giuffra et al. (2000) found that a feral pig sequence from Cook Island in Polynesia clustered with European domestic pig sequences. Analyses of nuclear gene sequences in conjunction with mtDNA sequences will also help in discriminating between European and Asian origins as for the porcine GPIP gene in the study of Giuffra et al. (2000). Analysis of microsatellite marker allele frequencies using the standard ISAG/FAO marker set (Li et al., 2000) will also assist in deciphering the relationships of these populations of pigs and are already underway for the Auckland Island population and are planned for the Kune Kune pigs. Jointly these studies will illuminate the history of Pacific island pigs, their geographic origins and genetic diversity.” (Gongora, 2002)

They conclude by stating that “Kune Kune pigs have Asian mitochondrial DNA but at this stage we cannot distinguish between i) Polynesian introduction of Asian pigs, ii) European introduction of pigs from Asia/Polynesia or iii) introgression of Asian mtDNA into European pigs in Europe in 17th century and subsequent introduction of these “European” pigs into New Zealand.” (Gongora, 2002) The link with the Kolbroek may give a hint of what actually happened.

Links with Captain Cook

A cursory survey of Captain Cook and pigs confirms the fact that he released pigs on the islands. He did this more than one time. The pigs could even have been from the Cape Of Good Hope. On this 3rd voyage to New Zealand in 1776, he was met by a ship in Cape Town that accompanied him to New Zealand. The ship was the Discovery, commanded by Charles Clerke. “The Discovery was the smallest of Cook’s ships and was manned by a crew of sixty-nine. The two ships were repaired and restocked with a large number of livestock and set off together for New Zealand [from Cape Town] ( December).” (http://www.captcook-ne.co.uk)

We also know that pigs were sent to New Zealand from Australia. In 1793, Governor King of Norfolk Island gave 12 pigs to Tukitahua, one of two northern Māori chiefs who had been kidnapped and taken to Norfolk Island. By 1795 only one animal was left. King then established relations with the northern chief Te Pahi, and sent a total of 56 pigs in three ships in 1804 and 1805. It is probably from these, and from being gifted between tribes, that pigs became established in the North Island. From 1805 Māori were trading pigs to Europeans.” (https://teara.govt.nz)

Still, it is unlikely that the Kunekune came from animals that were merely “released” on the islands. These animals reverted to the feral state. I also suspect that, as was the case along the South African coast, pigs that were given as a gift or traded were probably consumed. There must have been a reason, planning, purpose and some instruction that accompanied the exchange of pigs into the hands of a leader who could command the breeding of the animals. Such an example exists, and as we will see later, it relates to the one voyage of Cook that started at Gravesend.

“Two pigs were gifted to Māori by de Surville at Doubtless Bay in 1769. During Cook’s second and third voyages, a number of boars and sows were released – most in Queen Charlotte Sound, but two breeding pairs were given to the Hawke’s Bay chief Tuanui.” Cook’s first visit to Hawked Bay was in 1769 sailing in the Endeavour as part of his first Pacific voyage (1768-1771). We know that he released pigs on the South Island. “Wild pigs, in the South Island at least, may have originated from Cook’s voyages, and are generally known as Captain Cookers.” (https://teara.govt.nz)

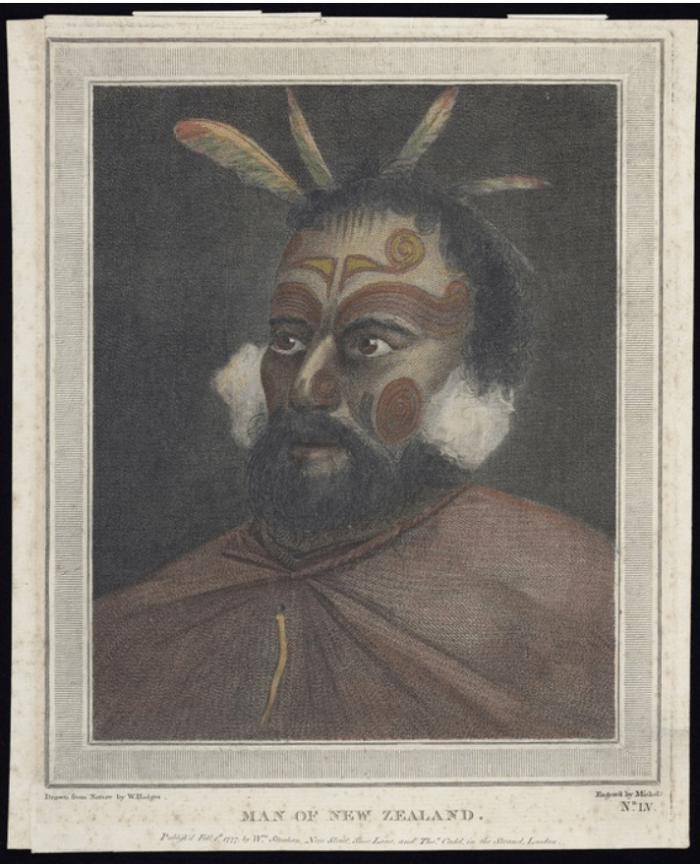

A portrait of Tuanui (also known as Rangituanui), principal chief of Ngati Hikatoa. The drawing by W. Hodges. Engrav’d by Michel. Published Feb 1st, 1777 by Wm. Strahan New Street, Shoe Lane, and Thos. Cadell in the Strand, London. No.LV. 1777

Cook gave him breeding pigs, a very interesting fact. There are accounts from New Zealand where Māori’s tried to pen up wild animals with no success. A leader such as Tuanui is exactly the kind of exchange one would expect to develop into the Māori-pig or the Kunekune.

Oral Tradition

I have great respect for oral traditions. Over the years I have seen how tenacious phrases and stories are over time, persist. It seems to me that the shorter the phrase, the simpler it is to pass on and, oftentimes, the more revealing it is of an actual event. This is more or less my approach with the Kolbroek and I was eager to see just how entrenched the theory is that Captain Cook released, not just any pig, but pigs from England on the shores of New Zealand that could have been the start of the Kunekune.

Searching through old newspapers yielded the following. From The Age (Melbourn, Victoria, Australia) (3) it was reported that “when Captain Cook landed in New Zealand during one of his great voyages of discovery, he set free on the shore several pigs which had been brought all the way from England to provide fresh meat on the voyage.” The wild pigs of New Zealand are according to the author, also descendants of the pigs that Cook released here. The link with England is of particular interest.

The Courrier (Waterloo, Iowa), 7 April 1886 calls the Māori Pig, “a descendant of one of Captain Cooks Pigs it may be – a swine, black but not completely, ill-shaped and clumsy, but apparently a perfectly happy pig leading, as he does, the life of a free and independent gentlemen, as does his mater, the Maori landowner and rejoicing in the grubbing up of abundant and gratuitous fern roots.” There is no reference to the pigs being from England and the author mentions the link between the Māori pig and Captain Cook as a possibility, but there can be little doubt we are talking about Kunekune here.

Studying old drawings can assist us as it does in our study of the development of pig breeds.

The image above can easily be a young Kunekune but then again, it could be any one of a number of smaller Chinese breeds. Photo by King, 2015).

The Gravesend Connection

The diary of events leading up to Cook’s first voyage gives us a connection with Gravesend.

| Jul. | 18 | Mon. | Pilot arrives to take Endeavour to the Downs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | Thu. | Sails from Deptford for Gallions Reach. | |

| 30 | Sat. | Sails from Gallions Reach to Gravesend. | |

| 31 | Sun. | Sails from Gravesend. | |

| Aug. | 3 | Wed. | Endeavour in the Downs. |

| 7 | Sun. | Cook joins Endeavour to commence Voyage. | |

| 8 | Mon. | Sails for Plymouth. |

Cook’s second and third voyage was undertaken, not from Gravesend, but from another location in Kent, The Downs. This means that in 1768 Captain Cook took pigs on board the HMS Endeavour, and in 1778, a mere 9 years later, the East Indiaman, Colebrook, took pigs on board from the exact same location in Kent. Could these have been Chinese Pigs, crossed with the same large English breed, possibly from the same boar resulting in the Kolbroek and the Kunekune?

Here is a possible reconstruction of events from my imagination. Village pigs at Gravesend in Kent, during the early 1700s, received a dominant pig boar that the villagers used to service their sows. This boar was probably owned by a wealthy local landowner. Beginning in the 1700s, Old English pig breeds were crossed with Chinese pigs, probably brought to English shores by the English East Indian Company. The navy used Gravesend to stock their ships with livestock, as did the English East Indian Company. Captain Cook took on board some of these pigs that managed to survive the journey without making it onto the sailers menu, all the way to New Zealand where they were given as a present to a powerful Maori chief who bred them. They later became the legendary Kunekune pigs.

It was the same kind of pigs that went aboard the East-Indiaman, the Colebrook, which sank off Cape Hangklip. Pigs from the sinking ship swam ashore at Kogel Bay, were taken in by runaway slaves (drosters) and became the legendary Kolbroek breed of the Cape of Good Hope (Kolbroek).

The breeds, as they exist today, share so many similarities that if one would simply look at them, one would say it is the same breed. One feature of the Kunekune which I have never found on the Kolbroek is that some of them develop a “wattle” or “tassel,” a fleshy appendage hanging from the lower jaw near the neck. This trait is becoming rare, but some of them have it. A veterinarian once told me that this tassel links them very directly with pigs that were found along the silk road in China. Much more work remains. Evidence may prove reality to be far removed from my imagination, but look at what we learned!

My theories about the origin of the Kunekune may or may not be accurate, but what is certain is that New Zealanders are “salt of the earth” kind of people. It was also here that I came to know one of the most colourful people to emerge from the curing industry – Aron Vecht!

Minette and I fell in love with New Zealand as we have never experienced it anywhere else in the world. The biggest reason is the people of this amazing land even though the land itself is of a beauty that is unrivalled. It was an honour to have married here and to forge a close connection with the people of this land. New Zealand has a unique place in the world community who have contained on its shores, the basic ingredients of bacon curing and living life to the fullest. We are stunned by the experience of the land and its people. I am excited about the prospect that one day you guys will visit these shores and have your own amazing experiences. I think we are building up a set of confidants around the world who will assist us to face any challenge that may be thrown our way at Woody’s.

Lots of love from Christchurch,

Dad and Minette.

Further Reading

- Chapter 06.01: Kolbroek

- Chapter 06.02: Kolbroek (A Follow-up)

- Chapter 13.15: The English pig with links to the Kolbroek and Kunekune

(c) eben van tonder

Stay in touch.

Join us on Facebook and stay up to date with our latest posts or subscribe using the tab in the right-hand column under the heading “FOLLOW BLOG VIA EMAIL”.

Notes

(2) Publication date, August 19-23, 2002

(3) Publication date, 14 July 1939.

(4) Nich did not introduce me to Aron Vecht. This part of my story is factional but neither Nich nor Aron Vecht are fictional and all other descriptions of these men are accurate.

References

APPENDIX TO THE JOURNALS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF NEW ZEALAND . SESSION II . , 1897 . VOL . III .

Sinclair, J. (Ed). 1897.Pigs Breeds and Management. Vinton and Co, London

Harris, J. (Ed.). c 1870. Harris on the pig. Breeding, rearing, management, and improvement. New York, Orange Judd, and company.

The New Zealand Official Yearbook, 1893.

http://www.majstro.com/dictionaries/Afrikaans-English/Slams

https://teara.govt.nz/en/kai-pakeha-introduced-foods/page-1

https://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/search/imagedetail.php?id=260

http://www.captcook-ne.co.uk/ccne/timeline/voyage3.htm

The Age (Melbourn, Victoria, Australia) of 14 July 1939, p 5.

Biology online. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

The Courrier (Waterloo, Iowa), 7 April 1886

Gongora, J., Garkavenko, O., Moran, C.. 2002. From the 7th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, August 19-23, 2002, Montpellier, France, Paper entitled

Origins of the Kune Kune and Auckland Island Pigs in New Zealand.

Green, G. L.. 1968. Full Many a Glorious Morning. Howard Timmins.

The Journal of Agriculture and Industry, Volume 3, 1899, By South Australia. Department of Agriculture, C. E. Bristow, Government Printers

King, C. M.., Gaukroger, D. J., Ritchie, N. A. (Editors), 2015. The Drama of Conservation, Springer.

The phylogenetic status of typical Chinese native pigs: analyzed by Asian and European pig mitochondrial genome sequences. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology volume 4, Article number: 9 (2013).

White, S.. 2011. From Globalized Pig Breeds to Capitalist Pigs: A Study in Animal Cultures and Evolutionary History, Vol. 16, No. 1 (JANUARY 2011), pp. 94-120, Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of Forest History Society and American Society for Environmental History, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23050648

Photo References

https://www3.stats.govt.nz/New_Zealand_Official_Yearbooks/1893/NZOYB_1893.html

http://mfo.me.uk/wiki/index.php?title=C%26T_Harris_%28Calne%29_Ltd